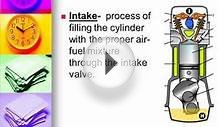

Suck, squeeze, bang, blow. These are the four strokes of the reciprocating, internal-combustion engine (ICE) that Nikolaus Otto patented in the 19th century. The action of the intake valves that allow an engine to breathe and the exhaust valves that let it expel spent gases were, until very recently, defined by a shaft of eccentric lobes rotating half as fast as the engine’s crankshaft.

Cams still spin half as fast as the crank in the modern engine, but advances like camshaft phasing, or changing the relative opening and closing of valves in relation to the crank position, thus improving efficiency and performance, are commonplace. Honda’s VTEC actually changes the cam profile, increasing valve-event duration and lift at high rpm. BMW and Nissan have variable intake-valve lift systems that actually control the amount of intake air, as opposed to a throttle plate.

If you can imagine an engine free of the mechanical constraints of a steel camshaft (or four), you have the basics of the Koenigsegg Freevalve engine. As opposed to a camshaft dictating valve position, each valve has its own actuator controlling the valve position and timing. The idea has been around for years, and many firms have worked on bringing it to market, but supercar maker Koenigsegg has spent the last 13 years working on a camless head, and it just released this nifty video:

Freevalve from Freevalve on Vimeo.

There are more potential advantages to a cylinder head of this design than we can list. In theory, a camless engine can run on any combination of its cylinders, with conventional or the more efficient Atkinson and forced-induction Miller cycles (thanks to their relatively bigger expansion ratios), and with lots of overlap, depending on the application. Or not. A naturally aspirated 1.5-liter four-cylinder capable of 40-plus mpg on two cylinders and well over 250 horsepower when wanted isn’t outside the realm of possibility. Only want to pump 87 octane? No problem, but when you decide to spring for the good, high-knock-resistance premium, your engine could instantly crank out more power, especially if there is a turbocharger in the mix.

When camless heads catch on—there’s no if—the EPA’s gas-guzzler tax could cease to exist; at minimum, there would need to be a comprehensive rewrite of those laws, because every engine could nurse its way through EPA testing. The potential is nearly limitless at both ends of the spectrum: efficiency and power.

There are a few small downsides, however. There is a draw from the engine to run the pneumatic (an air compressor/accumulator of some kind is needed) and oil actuators (another oil pump), but those losses aren’t nearly as large as the parasitic losses from the friction associated with driving cams, chains, and spring-loaded valves. Plus, those actuators are rather noisy and in their current state would never pass the public muster.

New technologies take a while to ripen before they’re ready to hit the produce stand. The good news is the ICE isn’t going anywhere soon. Aside from all the benefits, the camless head will also give the ICE a much-needed shot of adrenaline before electric motors take over the world.

RELATED VIDEO