According to government and industry sources, the time-honored internal combustion engine (ICE) could be honored with much more time – as in indefinitely.

According to government and industry sources, the time-honored internal combustion engine (ICE) could be honored with much more time – as in indefinitely.

While electrification enthusiasts have predicted a pending demise for the ICE, the U.S. Energy Information Agency predicts in 2035 that 99 percent of light-duty and heavy duty vehicles, particularly in commercial use, will still rely on fuel-burning engines.

To keep fossil tech evolving for commercial and passenger vehicles, innovations are being rolled out to squeak incremental gains, while research is ongoing to increase their future capabilities.

“Improving the efficiency of internal combustion engines is one of the most promising and cost-effective near- to mid-term approaches to increasing highway vehicles’ fuel economy, ” says the U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy.gov website. Lab tests, it adds, have shown fuel economy can be improved by more than 50 percent and even possibly 75 percent over today’s engines.

While we often hear of the government giving a plug for plug-ins, its playing all angles should not come as a surprise, even to electrification enthusiasts. Presently 99 percent of America’s 16.5-million annual passenger vehicle market still relies on the ICE – not to mention hybrids and plug-in hybrids which themselves use internal combustion engines.

But with next-generation lithium-ion batteries on the horizon for electrified passenger vehicles, and anything possible after that, it does remain to be seen how things actually unfold. Really, it’s a technological shakeout we’re in – with the entrenched ICE being tenaciously held onto, and those invested in it not relinquishing their grip willingly, nor are they being forced to.

On the contrary, federal Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) rules demanding “54.5” mpg – low 40s on the window sticker – by 2025 are pushing automakers toward electrification, but give them a way out, if they desire. The rules actually have been written so that a mere 1-3 percent of vehicles must resort to plug-in electrification, although more is encouraged.

There are 253 million cars and trucks on American roads today, and according to Energy.gov, nearly 60 percent of total U.S. oil consumption and more than a quarter of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions comes from on-road vehicles.

There are 253 million cars and trucks on American roads today, and according to Energy.gov, nearly 60 percent of total U.S. oil consumption and more than a quarter of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions comes from on-road vehicles.

Armchair pundits often suggest we should just cut through the Gordian knot with known plug-in technologies, but industry is heavily invested in the present paradigm, and wheels are turning slower than some who think like Elon Musk would desire.

With your taxpayer dollars behind them, the federal government is promoting an “all of the above” strategy that gives a leg up not just to plug-in battery tech, but also hydrogen fuel cells, alternative fuels, and the internal combustion engine.

According to the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, since October 2007 average window sticker fuel economy values on new cars sold in the U.S. have gone up only 5.3 mpg to 25.4 mpg as of June. This is true despite major automakers having had production-ready tech for 50-100-plus-mpg vehicles all along.

Like it or not, this is what we have in a world of politics, compromise, entrenched interests, and following are ways the ICE is maintaining its foothold in the western world.

Production Technologies

Automakers have an arsenal of technological choices enabling them to stay ahead of CAFE, California rules, and various global regulations dictating average across-the-board fleet mpg and CO2 improve year by year.

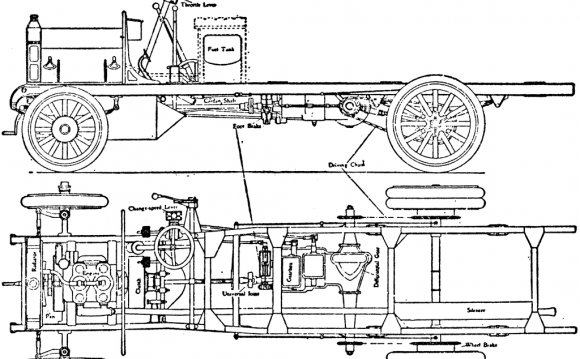

Advanced Engine Technologies

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, engine technologies stand to improve efficiency and save operational costs over vehicles’ lifetime. Federal efficiency and cost-saving estimates below are based on DoE assumptions of 166, 000 lifetime miles, fuel priced at .81, and compared to an average 22 mpg vehicle.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, engine technologies stand to improve efficiency and save operational costs over vehicles’ lifetime. Federal efficiency and cost-saving estimates below are based on DoE assumptions of 166, 000 lifetime miles, fuel priced at .81, and compared to an average 22 mpg vehicle.

1. Forced Induction

In simplest terms, supercharging and turbocharging are two means to compress more air and thereby more fuel into a combustion chamber.

Some fighter planes in World War II used forced induction, and the tech had been around before that, but it’s a finding computer-aided resurgence these days with the trend to downsize engines and cram more fuel and air in.

This gives smaller engines the power of larger engines while allowing automakers to submit them to relatively tame and legal drive cycles that may report remarkable mpg and CO2 scores.

Forced induction is an expedient way to serve up an engine that can offer satisfying power with better efficiency – just so long as the driver does not push the gas to the floor, at which point the maxim “your mileage may vary” comes back in full force.

Efficiency improvement potential: 2-6 percent

Lifetime cost savings: $400 – 1, 300

2. Cylinder Deactivation

Vehicles are increasingly seeing this computer-enabled trick employed that can make an eight-cylinder run on four cylinders, or a six-cylinder run on three cylinders under light load use, such as on the highway.

The technology can also be called “multiple displacement, ” or “displacement on demand, ” “active fuel management, ” or “variable cylinder management.”

It really is a decent concept too, as even, for example, a 450-horsepower Chevy Corvette C7 has been reported as returning over 30 mpg on a tame highway cruise which is amazing compared to what used to be expected.

Efficiency improvement potential: 4-10 percent

Lifetime cost savings: $800 – $2, 100

3. Gasoline Direct Injection

With this technology, fuel is injected directly into the intake port and mixed with air as the air-fuel mixture is drawn into the cylinder.

Also known as “direct fuel injection, ” and “spark ignition direct injection (SIDI)” the setup makes the fuel-air mixture a bit cooler enabling higher a compression ratio and increased combustion efficiency.

This means higher performance and less fuel consumption.

Efficiency improvement potential: 2-3 percent

Lifetime cost savings: $400 – $600

4. Variable-Valve Timing and Lift (VVTL)

Intake valves control fresh air into the cylinders and exhaust valves control the flow of exhaust out of the cylinders.

When and how long the intake and exhaust valves open (timing) and how much the valves move (lift) both affect engine efficiency.

VVTL automatically optimizes valve timing and lift for varying engine speed and power.

It contrasts with traditional fixed valve timing and lift settings, which compromise efficiency between high and low engine speeds.

This tech includes “variable valve actuation, ” “variable-cam timing, ” “cam phasing, ” “variable valve timing and lift electronic control (VTEC, VANOS, VVT-i), ” etc.

RELATED VIDEO

A hybrid vehicle is a vehicle that uses two or more distinct power sources to move the vehicle. The term most commonly refers to hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), which combine an internal combustion engine and one or more electric motors.

A hybrid vehicle is a vehicle that uses two or more distinct power sources to move the vehicle. The term most commonly refers to hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), which combine an internal combustion engine and one or more electric motors. A battery electric vehicle, or BEV, is a type of electric vehicle (EV) that uses chemical energy stored in rechargeable battery packs. BEVs use electric motors and motor controllers instead of internal combustion engines (ICEs) for propulsion.

A battery electric vehicle, or BEV, is a type of electric vehicle (EV) that uses chemical energy stored in rechargeable battery packs. BEVs use electric motors and motor controllers instead of internal combustion engines (ICEs) for propulsion.