St. Patrick's Day 2012 in St. Paul was the crowning moment of one of Minnesota's mildest winters: Jubilant parade spectators wore flip flops, Miss Shamrock beamed in sleeveless, emerald satin, and the beer never tasted so refreshing as temperatures hit 80 degrees.

Three months later, the dazzling sunlight was nowhere to be found when rain sheets pummeled the Duluth area. Muddy torrents of chocolate, fuming floodwaters tore through town, leaving shock and devastation.

Both extremes happened in a Minnesota our ancestors never knew. It's warmer, especially in the winter, and rising global temperatures have stacked the deck in favor of heavier rains.

Even in a land used to being wowed by the weather, the month-to-month, year-to-year roller coaster ride is more thrilling — and terrifying — than it's ever been.

Data collected systematically over nearly two centuries make it irrefutable: Minnesota's climate has changed and so has the state's diverse web of life.

Cold weather species like moose and lake trout are disappearing. Maple trees are migrating north. Bugs once killed off by winter are surviving to destroy tens of thousands of acres of forest. Lake Superior is one of the fastest warming lakes on the planet.

Climate scientists get nervous attributing one really warm month or one big storm to climate change. But undeniable trends are giving Minnesotans reason to look out the window every day and wonder whether climate change has something to do with what they see.

Although 2014 was colder than normal here, most of the rest of the world heated up, making the year the warmest on record globally. The world's temperature has been rising almost a third of a degree per decade since 1970, and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, considered the main driver of this change, has reached its highest level in at least 800, 000 years.

Luther Opjorden stood next to the weather observation station on his farm on Oct. 27, 2014. Yi-Chin Lee / MPR NewsEfforts by some world leaders to address it have picked up urgency. Late last year, President Obama announced an agreement with China to take steps to deal with carbon emissions, and last week he urged India to do more as well.

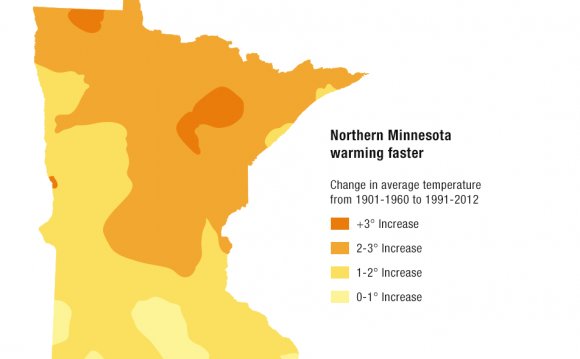

Compared to most other states, Minnesota has experienced faster temperature increases and greater increases in big rainstorms. In response to the change, the state in 2007 set goals aimed at reducing carbon emissions. And since then scientists have fine-tuned research; health, environment and other officials have urged new policies to address the change. At the same time, foresters, farmers, business and government leaders and others have begun adapting to change — whether they accept the term "climate change" or not — to prepare for impacts that could cost billions of dollars in coming years.

Climate: The weather's batting average

Weather and climate are inextricably linked, which is why countless conversations about climate change go something like this, says state climatologist Greg Spoden: " 'Hey, look it's very hot today, isn' t this an example of climate change?' Or, 'Hey, it's very cold today, where is your climate change, Buddy?'"

Think baseball, Spoden says. "Weather is the individual at-bats and the individual games. The batting averages and the long-term statistics are the climate."

"If your best hitter goes 0-for-4, that's not necessarily a trend and you' re not going to trade him or cut him. It's a body of work over a season or many seasons."

Minnesota's climate record goes back further than baseball statistics. A fur trader in the Red River Valley started recording temperature and precipitation data in 1807 (1). A surgeon at Fort Snelling recorded the first readings there in 1820. Today the scorekeepers include 163 volunteer weather observers scattered around Minnesota who send information daily to the National Weather Service. More than 50 sites have collected data for more than a century, including Milan, a town of 350 people in western Minnesota.

Opjorden's daily notes Yi-Chin Lee / MPR News"You really don't notice it, but a degree or two over the long haul is significant, " Opjorden said.

"We are very blessed in Minnesota to have the length of records that we do, " said Michelle Margraf, the National Weather Service's coordinator of weather observers for part of Minnesota. "We're just grateful for the people who had the foresight back then to start marking down the daily information."

Jaime Chismar for MPR NewsIt's warmer, especially in winter

Amateur phenologist John Latimer checked the ice depth at a lake near his home Nov. 12, 2014 near Grand Rapids, Minn. Derek Montgomery / For MPR News"The wintertime signal is the most robust in the data record, particularly as you go north. Northern Minnesota is definitely bearing the brunt of that warming, " he said. One possible explanation for that, he said, is that snow and ice normally cover northern climates like Minnesota in the winter, acting like a mirror to reflect the sun's rays. "When it's warming, you can get less snow, and the fact that you have less snow, uncovers the surface below it, which might be less reflective, and that causes additional warming, which melts more snow and it goes around and around, " Snyder said. (10) In the past 40 years, Minnesota's winters have warmed faster than any other state. (11) More heat affects Minnesota in countless ways. An obvious one: less ice on the state's vaunted 10, 000 lakes.

"This lake has been on average a half a day later a year for 30 years, " he said, standing on two-inch thick ice late last fall. " So it's 15 days later now than it used to be."

Ice out on lake Osakis from 1867 to 2014. Jaime Chismar for MPR News Distribution of Lyme disease by county. Jaime Chismar for MPR NewsScientists predict Minnesota's beloved north woods — the boreal forest of red and jack pine, spruce, birch and aspen will shift northward as the climate warms.

RELATED VIDEO

Minnesota (/mɪnɨˈsoʊtə/) is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state on May 11, 1858. Known as the "Land of 10,000 Lakes", the...

Minnesota (/mɪnɨˈsoʊtə/) is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state on May 11, 1858. Known as the "Land of 10,000 Lakes", the...

Fridley is a city in Anoka County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 27,208 at the 2010 census. It was incorporated in 1949 as a village and became a city in 1957. It is part of the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area. Fridley is a "first ring" or "inner ring...

Fridley is a city in Anoka County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 27,208 at the 2010 census. It was incorporated in 1949 as a village and became a city in 1957. It is part of the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area. Fridley is a "first ring" or "inner ring...